Recursion

What is recursion?

Informally, a recursion is a formula which self-references itself.

The following is a basic recursive function: $$ \begin{align} f(0) &= c \ f(n+1) &= G(f(n)) \end{align} $$ This can also be views as an equation system, where the unknown term is \(f\) (\(f\) can be a function).

This is the equivalent haskell code:

primRec :: (Integer -> Integer) -> Integer -> Integer -> Integer

primRec g c n

| n == 0 = c

| otherwise = g $ rec_ (n-1)

where

rec_ = primRec g c

\(n+1\) or \(n-1\)

The following implements an exponential function: $$ 2^0 &= 1\ 2^{n} &= 2 \cdot 2^{(n - 1)} $$

exp2 0 = 1

exp2 n = 2 * exp2 (n-1)

{- this can also be defined with primRec from above -}

exp2' = primRec ((*) 2) 1

However, we can also implment this in a more mathematical way: $$ 2^0 &= 1\ 2^{(n+1)} &=2\cdot 2^n $$

data Nat

= N

| S Nat

deriving (Show, Eq)

expN :: Nat -> Nat

expN N = S N

expN (S n) = mulN (S (S N)) (expN n)

Types of Recursions

Primitive Recursion

This adds \(\vec x\), representing additional parameters to the function. However, \(\vec x\) cannot be modified by \(G\). Furthermore, \(G\) also has access to the current \(n\).

This allows us to implement x to the power to y like the following:

In the case of the factorial function, the \(n\) parameter can be useful as well:

(G should be defined as \(G(a, n) = n \cdot a\))

However, this does not allow all recursive function. For example, a the fibonacci function requires access to both the last and the second last value.

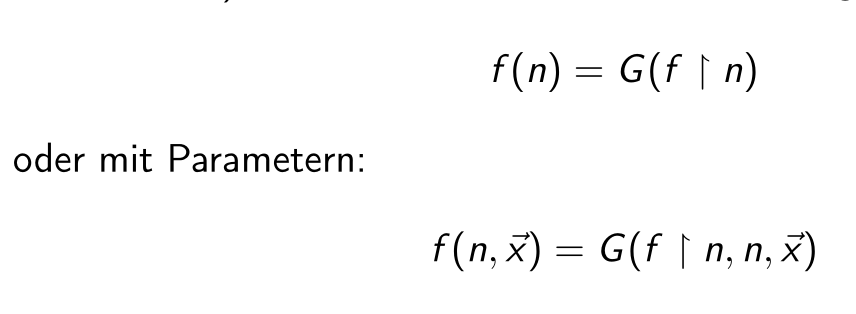

Recursive Value Recursion (“Wertverlaufsrekursion”)

A recursive value recursion is similar to a primitive recursion, with the key difference that \(G\) can access all past values instead of just the last one.

In theory, since finite sequences can be encoded as numbers, every recursive value recursion can be encoded as a primitive recursion.

The following shows an example in haskell:

valueRec :: ([Integer] -> Integer) -> Integer -> Integer

valueRec g n = g [ valueRec g (n-i) | i <- [1..n]]

fib = valueRec g

where

g [] = 1

g [_] = 1

g (x:y:_) = x + y

General Recursion ("Allgemeine Rekursion")

If the schemes from above are not followed

Tail Recursion (Endrekursion)

A function is tail-recursive, if the last expression in every branch is the recursive call.

Accumulator Pattern

-- This is **not** tail recursive, because the last expression is (+)

sum_ :: [Integer] -> Integer

sum [] = 0

sum_ (x:xs) = x + (sum_ xs)

-- This is recursive

sumTR_ :: Integer -> [Integer] -> Integer

sumTR_ acc [] = acc

sumTR_ acc (x : xs) = sumTR_ (x + acc) xs

sumTR = sumTR_ 0

-- the following defines a factorial function, using the "accumulator pattern"

fakTR :: Integer -> Integer

fakTR = fakTR_ 1

where

fakTR_ :: Integer -> Integer -> Integer

fakTR_ acc 0 = acc

fakTR_ acc n = fakTR_ (n * acc) (n - 1)

-- the following is an power function

pow_ :: Integer -> Integer -> Integer

pow_ = powTR 1

where

powTR :: Integer -> Integer -> Integer -> Integer

powTR acc _ 0 = acc

powTR acc b e = powTR (b * acc) b (e - 1)

-- this is a second iteration that is slightly cleand up

-- (b has been pulled out of powTR)

pow_ :: Integer -> Integer -> Integer

pow_ b = powTR 1

where

powTR :: Integer -> Integer -> Integer

powTR acc _ 0 = acc

powTR acc e = powTR (b * acc) (e - 1)

The following is an example, where a Bool is used as an accumulator:

isPalindrome :: String -> Bool

isPalindrome w

| l < 2 = True

-- this is technically also a tail recursion, since && short-circuits

| otherwise = w0 == wE && isPalindrome w'

where

l = length w

w0 = head w

wE = last w

w' = tail $ init w -- w without the head or tail

isPalindrome' :: String -> Bool

isPalindrome' = isPalindromeTR True

isPalindromeTR :: Bool -> String -> Bool

isPalindromeTR acc w

| l < 2 = acc

| otherwise = isPalindromTR (acc && w0 == wE) w'

where

l = length w

w0 = head w

wE = last w

w' = tail $ init w -- w without the head or tail

The fibonacci sequence needs two accumulator, since the last and second to last element has to be accessed.

fibs n

| n < 2 = 1

| otherwise = fibs (n - 1) + fibs (n - 2)

-- tail recursive

-- fibs 1 1 n is the base case for acc1 and acc2

fibsAcc acc1 acc2 n

| n < 2 = acc1

| otherwise = fibAcc (acc1 + acc2) acc1 (n - 1)

Continuation Pattern

At times it can be easier to represent the work that still needs to be done as a parameter. This is the difference between the continuation pattern and the accumulator pattern (where the computed value is represented as a parameter).

fakC :: Integer -> Integer

fakC = fakC_ ( const 1)

where

fakC_ f n

| n < 1 = f n

| otherwise = fakC_ (\ x -> n * ( f x ) ) $ n - 1

The following examples show why it can advantageous to use the continuation pattern instead of the accumulator pattern.

myMap :: (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

myMap f [] = []

myMap f (x : xs) = (f x) : (myMap f xs)

-- with the accumulator pattern

myMap' (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

myMap' f = myMapAcc []

myMapAcc :: [b] -> [a] -> [b]

myMapAcc acc [] = reverse acc -- the reverse is necessary since we add

myMapAcc acc (a:ax) = myMapAcc (f a : acc) ax

-- with the continuation pattern

myMap' (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

myMap' f = myMapCont id

myMapCont :: ([a] -> [b]) -> [a] -> [b]

myMapCont cont [] = cont []

myMapCont cont (a:ax) = myMapCont (\list -> cont (f x : list)) ax

-- We have more flexibility in the lambda expression, since cont is not a recursive

-- call

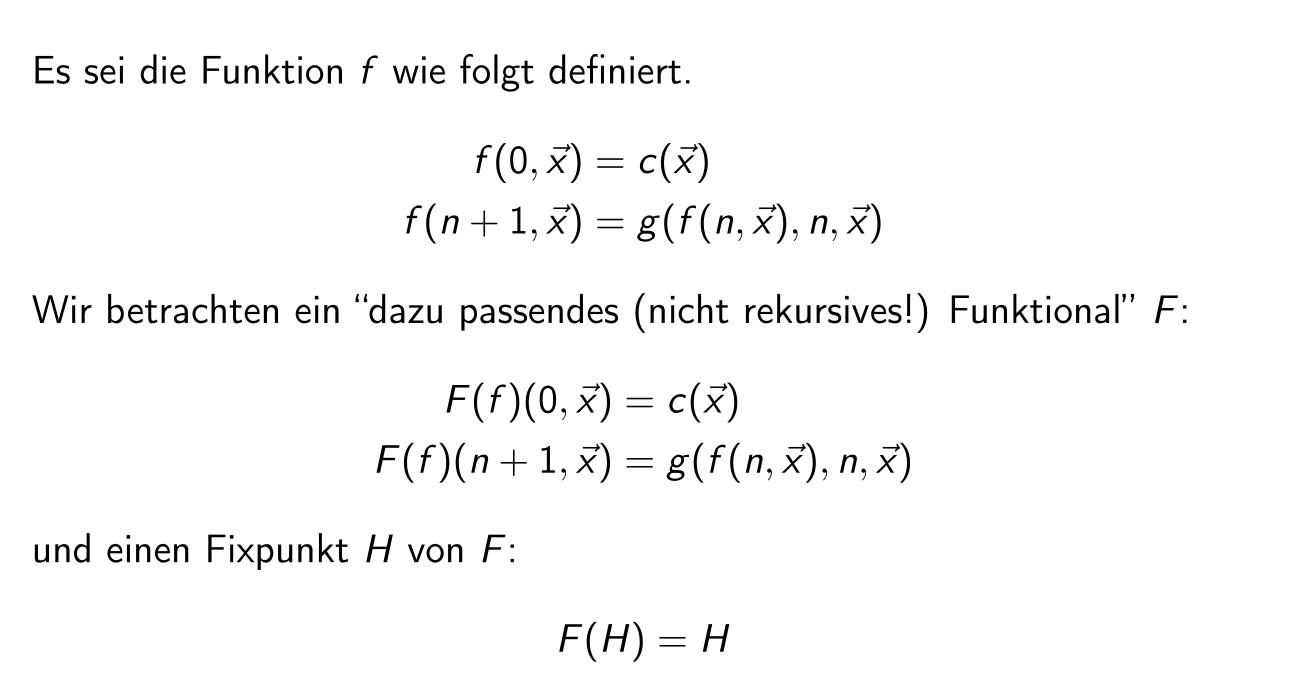

Fix Points

A fix point of a function \(F: X \to Y\) is where \(F(x) = x\).

As an example, the function \(id\) has a fix point for every argument. More graphically, the fix point of is where the graph of \(F\) crosses the diagonal.

A fix point function would be expF h = h . Importantly, \(h\) is a function and expF h is a partially applied function.

The following is fix point for a function f. It is essentially a recursion with out a base case. If applied to expF, then the base case of expF can be used by fix.

fix :: (t -> t) -> t

fix f = f (fix f)

-- alternatively, the type can also be expressed as following, where t = t1 -> t2

fix' :: ((t1 -> t2) -> t1 -> t2) -> t1 -> t2

fix' f x = f (fix f) x

For example:

fibs n

| n < 2 = 1

| otherwise = fibs (n-1) + fibs (n-2)

-- in the following example, every recursive call is replaced by `f`

-- This then yields the "Funktional" of fibs

fibF f n

| n < 2 = 1

| otherwise = f (n-1) + f (n-2)

-- to use fibF, it has to be applied to fix. This reintroduces the recursion

fix fibF = fibs

Even if Haskell didn't support recursion and would only support the fix function as part of the standard library, we still could write recursive functions using the trick above and the fix function.

The following shows why this works every time:

Memorisation

Memorisation can be implemented using fix points and a functional. An issue which arises with recursive function, is that the recursive call won't be memorisation. However, a functional isn't recursive by itself. Rather it uses a function passed as a parameter. This allows writing a memonisation function which inject itself into the recursive call.

General Fold

To generalise a fold function for a custom type T, the following steps can be followed:

- Analyse the type signature of the constructors of

T - Create function signatures for each constructor of

Twith the same parameters as the constructor. Instances ofTin the constructor should be rewritten to a type parameter. - Write a fold function, which takes a function for each constructor with the respective signature and an instance of

T

The following examples shows how a general fold function can be generated for the BTree type.

To create a fold, analyse each constructor

Then the fold function is