Cloud Native Application

A cloud native application is an application optimised for running in the cloud (IaaS or PaaS). A cloud native application exploits all cloud computing principles.

The principal goal is to exploit the economic value proposition of cloud computing, e.g. having fast life-cycles. To do this, each phase in the life-cycle of the application needs to be optimised for running in a cloud environment. Typically, cloud native apps are distributed systems.

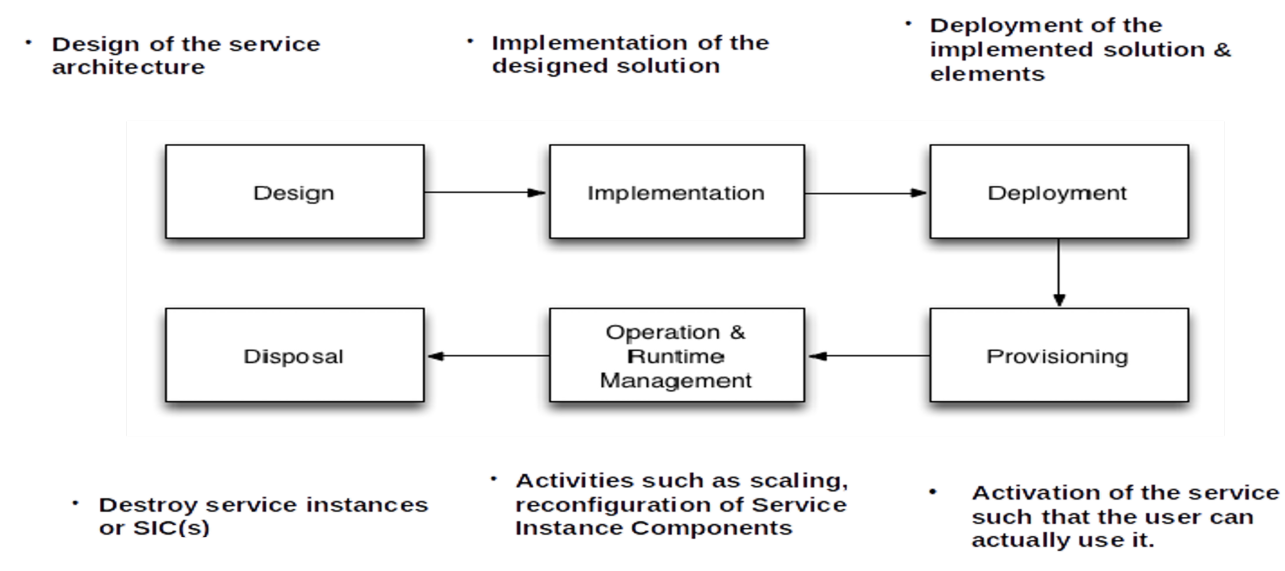

The following diagram shows the life-cycle of a cloud application:

(The difference between deployment and provisioning is that deployment deploys it on the hardware, but the service isn't yet available to the user. When provisioned, the service is actually accessible)

- Architecture: cloud native application needs to be designed for scalability and resilience (if one service goes down, another one can take over). This favours a service oriented architecture (e.g. micro-services)

- Organisation: Teams need to be (re-)organised around business capabilities (like a feature). This means the DB engineer and the front-end dev are working on the same team if they are working on the same feature

- Process: There needs to be automated software development, deployment and management pipeline

Service Oriented Architecture (SOA)

SAO Principles:

- standardised protocols (e.g. SOAP, REST, ...)

How the services inter-opt with each other - abstraction

A service should hide its internal structure and only provide a defined API-surface - Loose coupling

- Reusability

- Composability

- Stateless service

The state of an service should never be stored in the service itself. Instead, it should be stored in a DB, or other service. - Discoverable service

A service should be discoverable via a mechanism

Micro-Services

The micro-service architecture is a SOA architectural style with some additional points:

- Each service is "small" and dedicated to one thing (small doesn't necessarily mean not a lot of code, but it should be hyper-focused on one thing)

- Each service runs in its own process and can manage itself (self-composed in its own process)

- Each service is communicating with lightweight (e.g. simple and easy) mechanisms (e.g. REST APIs)

- Each service can be deployed independently in a fully automatic way

- Minimal centralised management of the services is required

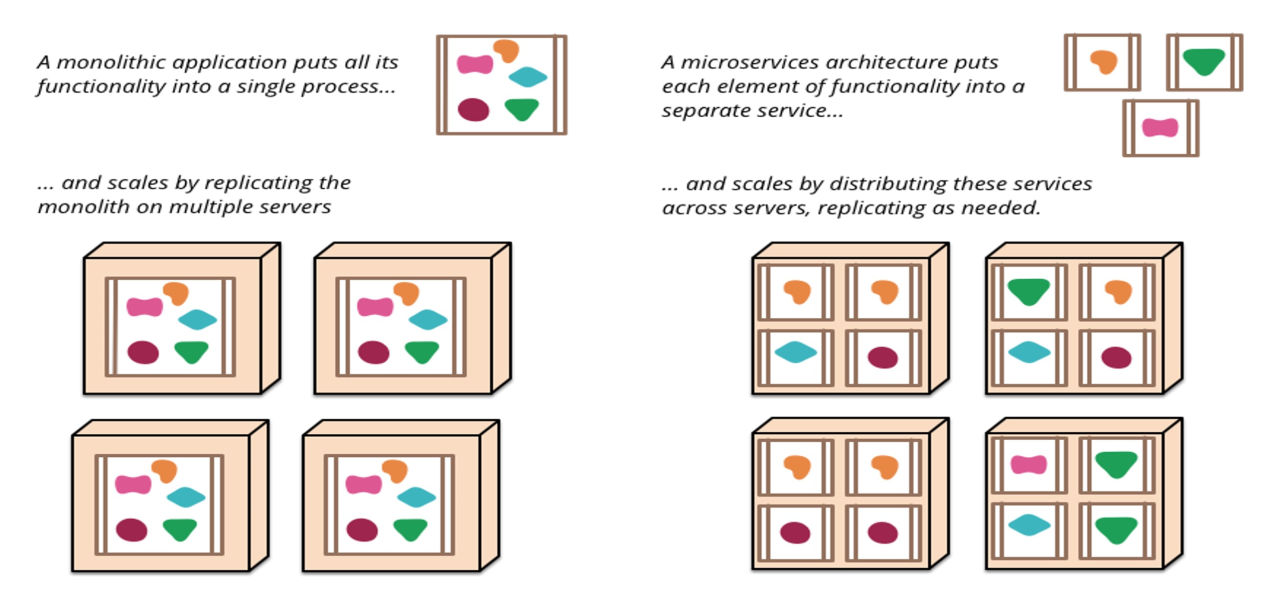

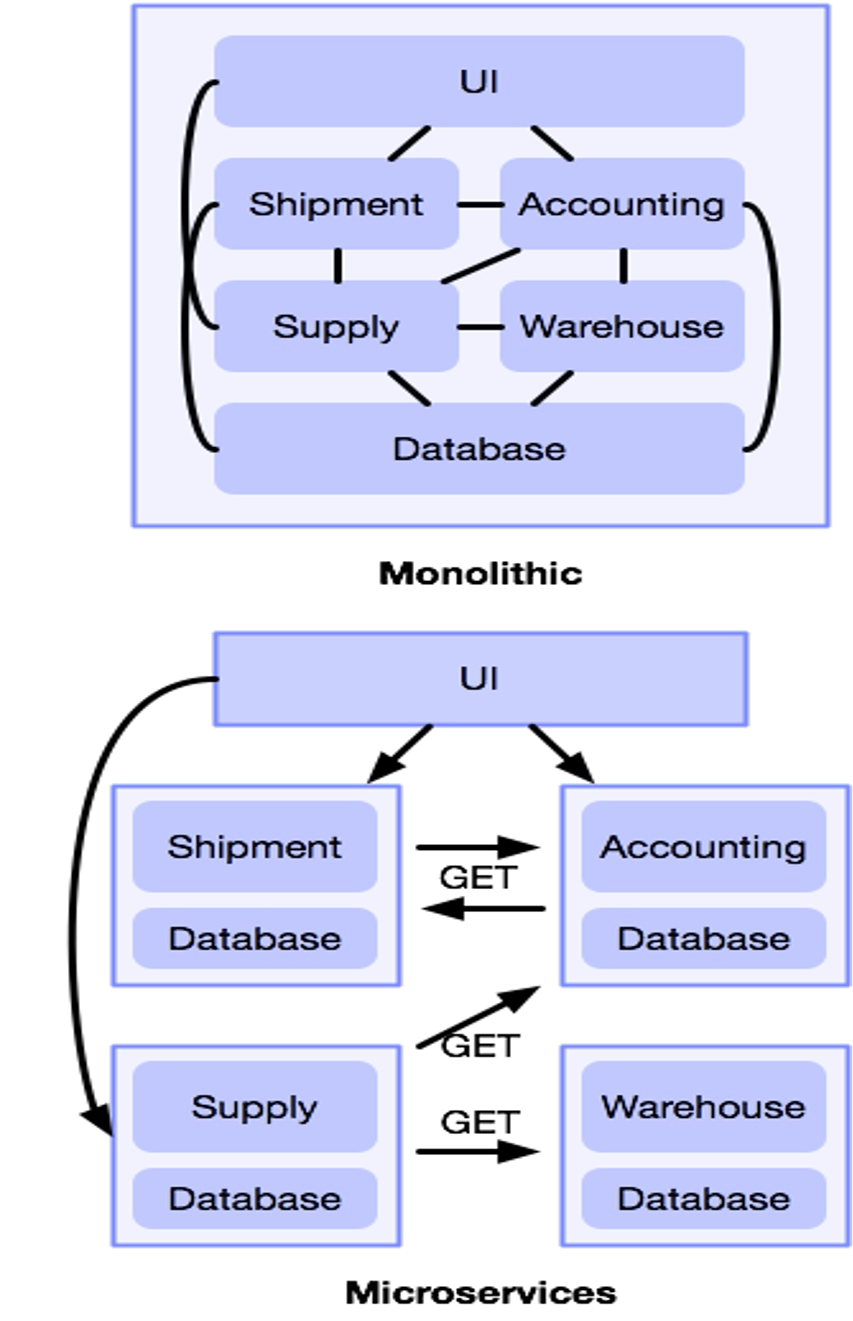

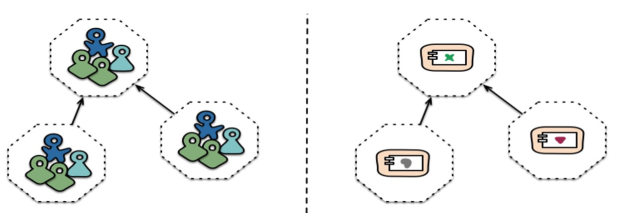

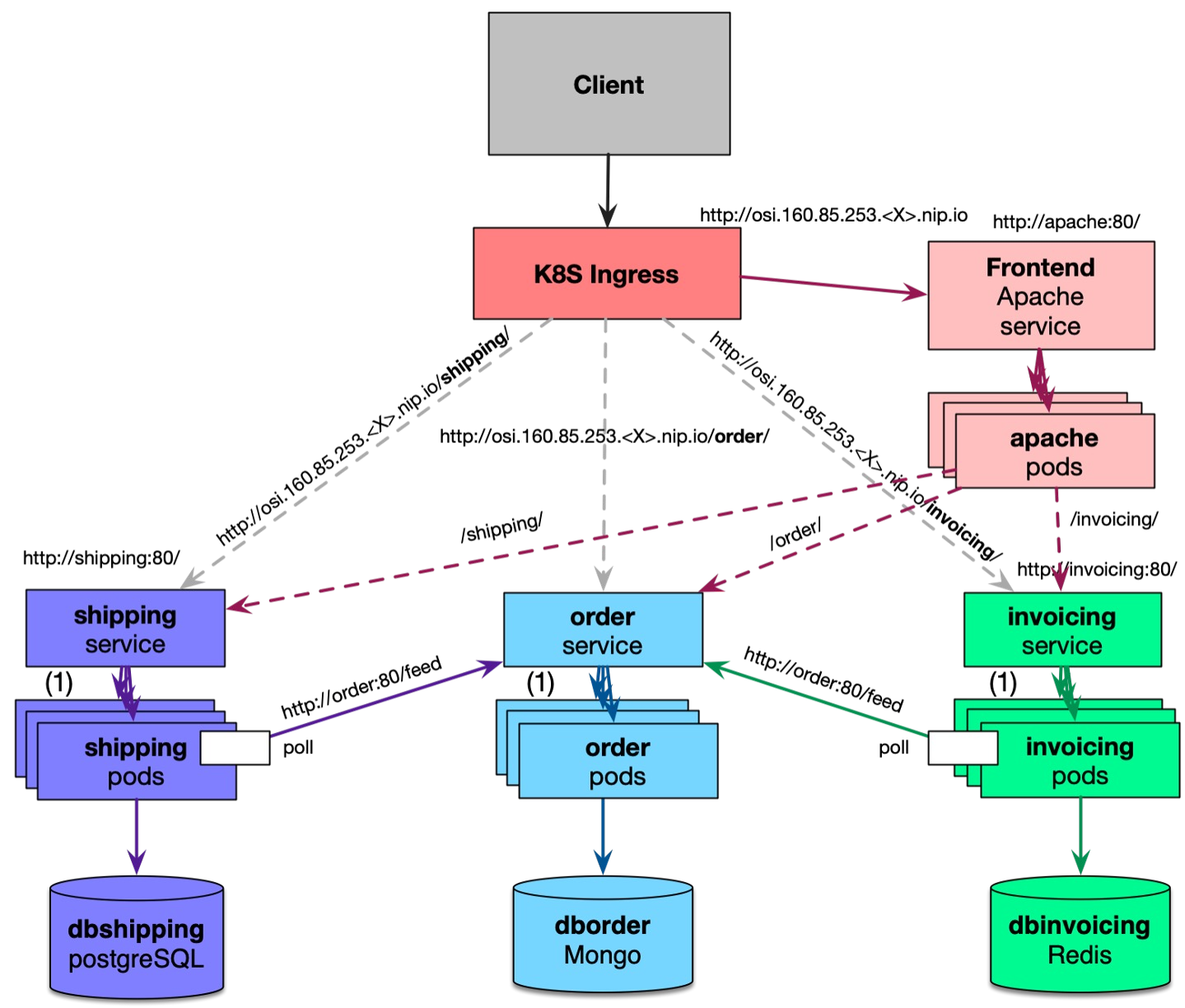

On the left side, a monolithic application is depicted. All features are packed into one process and it scales by replicating the entire application. On the right side, a micro-service architecture is shown and each individual service can be scaled independently of each other.

The following shows the difference between an application implemented as a monolith and as a micro-service architecture.

Conway's Law

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.

If an organisation is split into UI specialists, middleware specialists and DB admins, the application also reflects that structure. This is burdensome, as simple changes require cross-team approval.

In the (micro)service approach, each team is split along features (business capabilities). A team member can belong to multiple teams. Importantly, teams are cross-functional. Additionally, a team shouldn't be larger than how many people can be fed by two pizzas.

CNA Principles (12 Factor)

The following principles where developed by Heroku in 2011. See https://12factor.net/

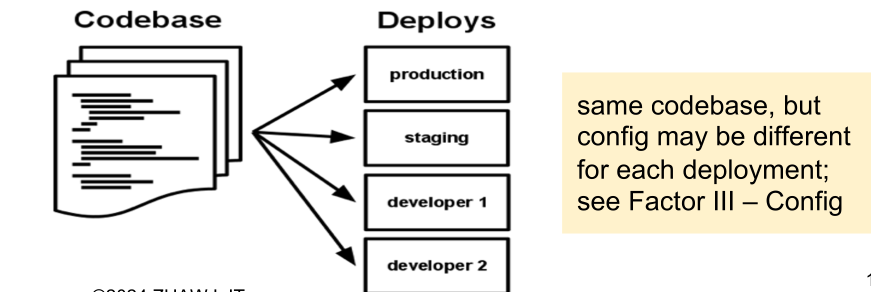

Codebase

One codebase tracked in revision control, many deploys. Importantly, the same code base is used for each customer.

Dependencies

All dependencies are explicitly declared and are isolated (both are required). Thus the application cannot depend on system-wide dependencies. This simplifies the setup and avoids sudden surprises when external dependencies inevitable change.

Dependencies can be specified with different tools:

- Java: pom.xml for dependencies and the JVM for the isolation

- C: autoconf for dependencies and static linking for isolation

- In general: Dockerfiles for dependencies and container-images for isolation

- Alternatively, build automation (ansible, ...) for dependencies and VM images for isolation

In general, wildcard declarations should be avoided at all cost.

Config

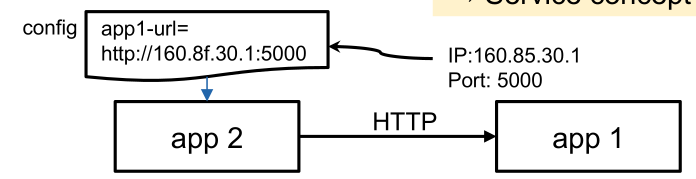

Everything that's likely to change between deployments should be stored in an external configuration, and not configured in the code.

This likely includes:

- Resources like databases and other backing services

- Credentials to external services (e.g. Amazon S3, Twitter, ...)

- Per-deploy values (e.g. canonical hostname, ...)

These configurations are strictly separated from the code and are injected into the environment. 12-Factor recommends doing this with environment variables, since they are easy to change without changing code, and they are unlikely to be checked into a repository.

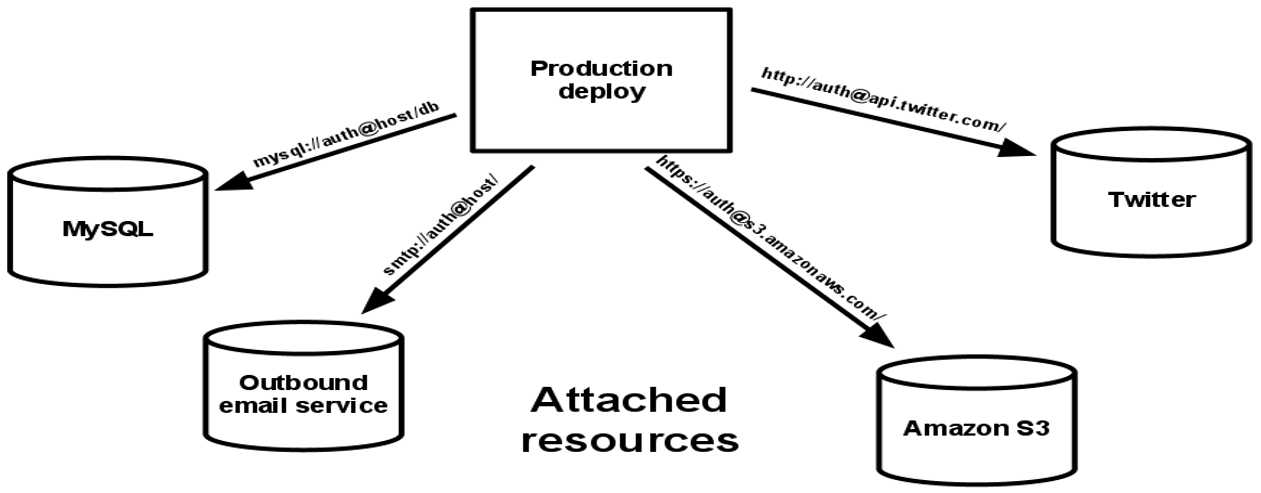

Backing Services

Backing services should be treated as an attached resource and need to be configurable as a URL. Importantly, no distinction is made between local and third-party services.

A backing service is any service the app consumes over the network during its normal operation (DB, monitoring, SMTP server, cache...)

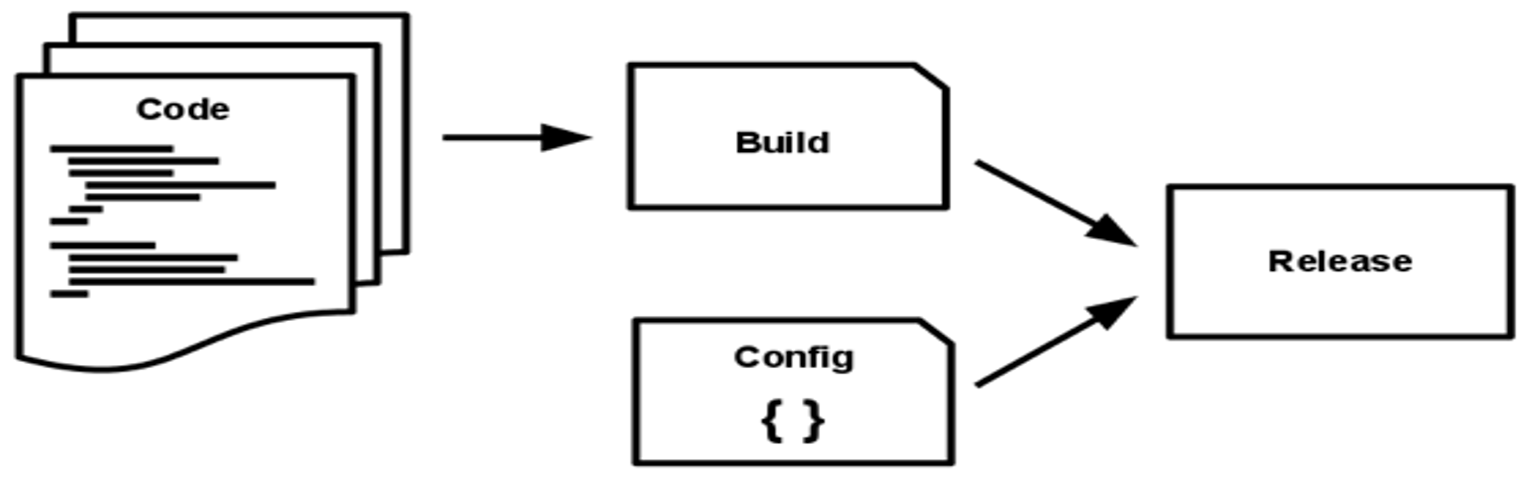

Build, Release, Run

Building, releasing and running are separated stages. This enables building the image once, then putting it into testing. After testing, the image can be put into production.

This is most likely an artefact of the past, when it was common to directly upload files to the production server.

Processes

Services (processes) are stateless and share nothing.

- A service never assumes that anything is cached in memory or on disk. This enables that a request can go to any instance, since the instance didn't cache anything

- Any persistent data must be stored in a stateful backing service

Port Binding

A service is completely self-contained and does not rely on the presence of a webserver in the environment.

A service can become the backing service for another app. Then the backing service's URL is provided to the service using the service.

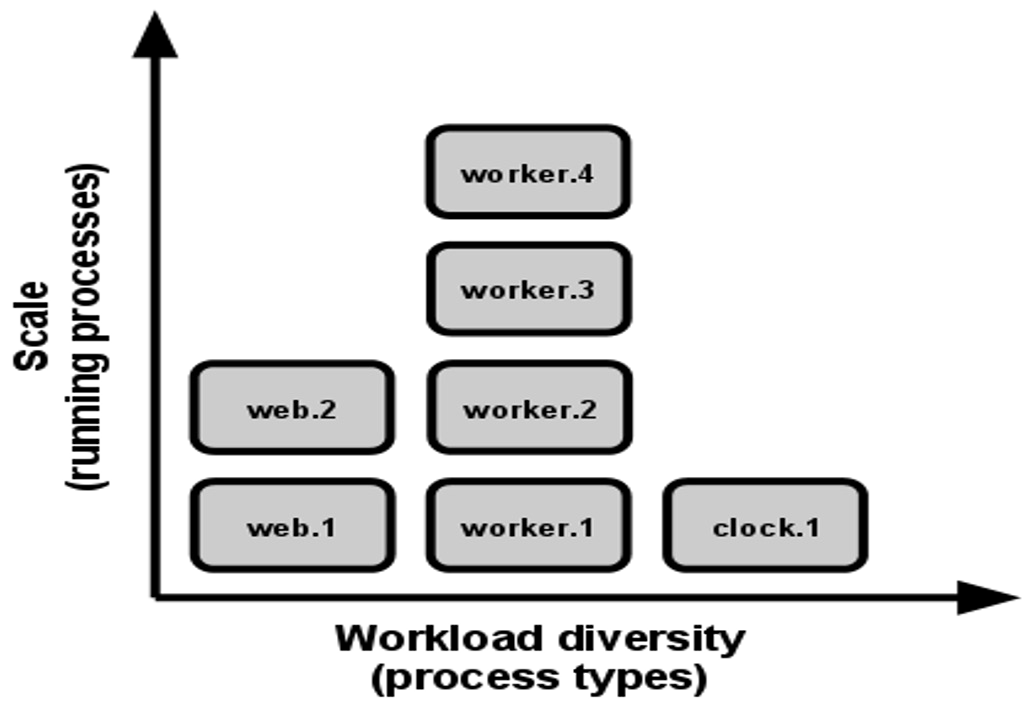

Concurrency

Each server can scale individually and horizontally (adding more instances).

Disposability

A service needs to be able to start and stop at any time. When receving a termination signal (e.g. SIGTERM), resources should be freed, the service should unsubscribe from message channels and more.

Additionally, the app should be robust against sudden death, in the case of a failure of the underlying hardware.

Dev/Prod Parity

Development, staging and production environment should be as similar as possible. This enables effective continuous delivery and deployment and avoid gaps between development and production.

- Avoid time gap: Write code and have it deployed within hours

- Avoid personnel gap: developers who wrote code are closely involved in deploying it and watching its behaviour in production

- Avoid tool gap: Use the same tools in development and production

Logs

Logs should be treated as event streams.

A service should never concern itself with routing or storage of its log output stream. Instead, the environment captures the logs and collated them together for viewing and for long-term archival.

Admin Processes

Management tasks (e.g. deployment or modifying DB structure) are executed as a one-off service and not part of the long-running services. Thus, services don't do migration themselves, since this could lead to disaster when the other replicas still require the old DB structure.

These tasks should be tested on a copy of the environment with the same release, codebase and config.

Cloud Patterns

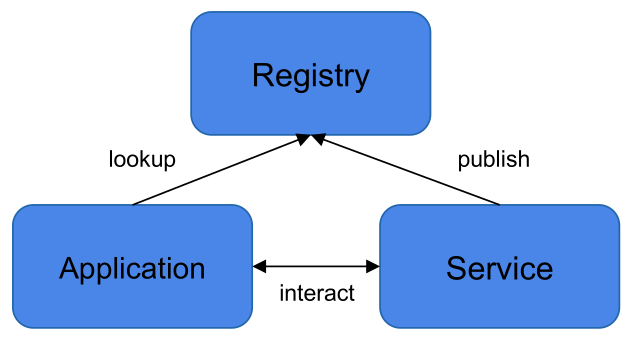

Service Registry

In a service-oriented architecture, one uses many services, runs many service instances and it can be a challenge to keep track of all of them.

A service registry maintains the state information of each service instance. It stores information like:

- What type of service is provided by an instance

- What is the function offered

- How to reach the instance

- How to talk to the instance (e.g. port, address)

- What is the state of the instance

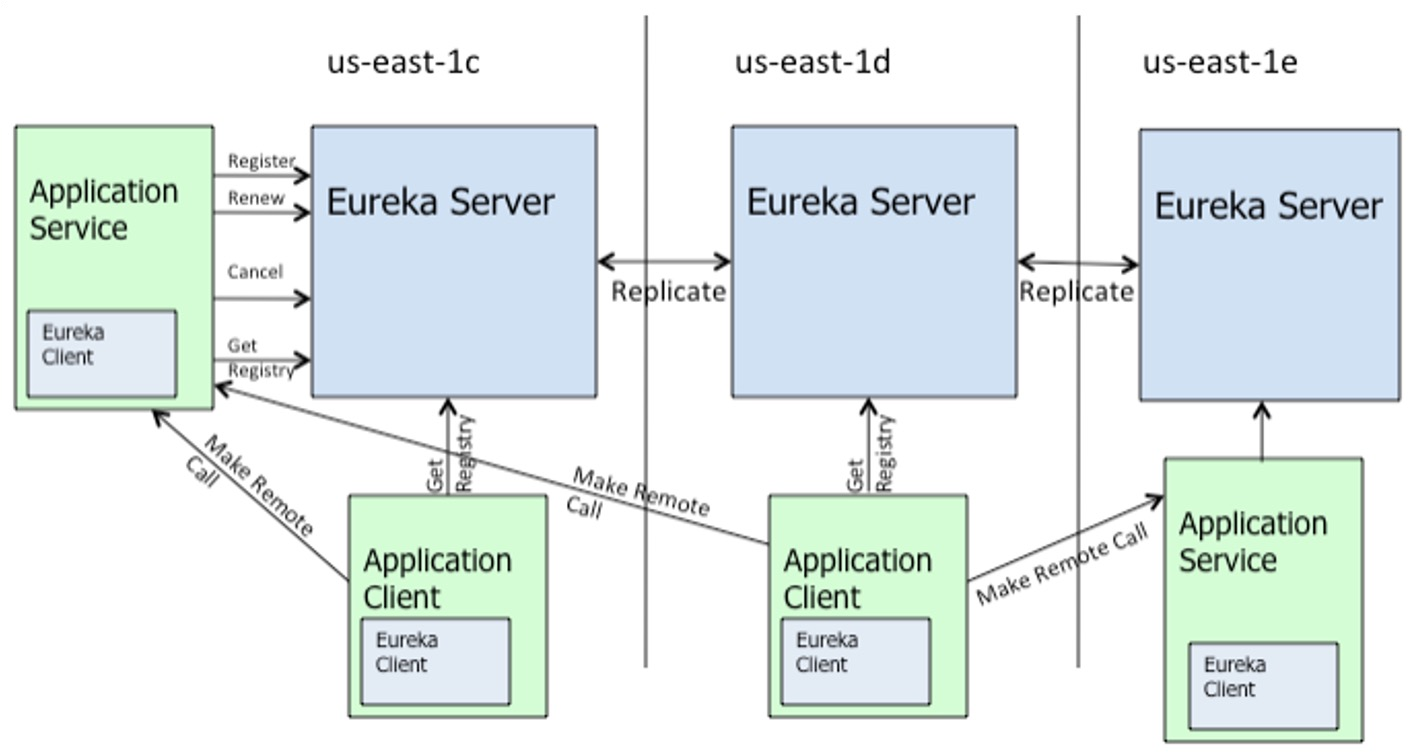

As can be seen in the diagram below, each service publishes their information to the registry. If an application (or another service) wants to interact with the service, they first look up the necessary information and then use that to communicate directly with the service.

There are many different service registries, like Netflix's Eureka, etcd or many more. The benefit of using a separate service registry than Kuberentes' built in registry, is that more information can be put into and read from the registry.

Eureka

An example implementation could consist of a REST API that offers a few actions to interacting with the registry:

register: Instance registers its connection endpoints and datarenew: Maintain the registration using a heartbeatcancel: Gracefully remove registrationgetRegistry: Function for querying available instances

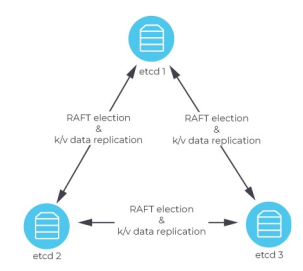

etcd

etcd is a distributed key-value store. The keys are strings and can be nested and folders can be used to organise the keys. Values can be pretty much anything.

Apart from setting and getting values, keys can also be watched. This enables using etcd as a message queue.

# sets the message key to "Hello world"

curl http://$HOST:2379/v2/keys/message -XPUT -d value="Hello world"

# gets the message key

curl http://$HOST:2379/v2/keys/message -XGET

# folder management

etcdctl mkdir /folder

etcdctl ls /folder

curl http://$HOST:2379/v2/keys/message?watch=true -XGET

# this will execute the command after the "--" when the key is changing

etcdctl exec-watch /folder/key -- /bin/bash -c "touch /tmp/test"

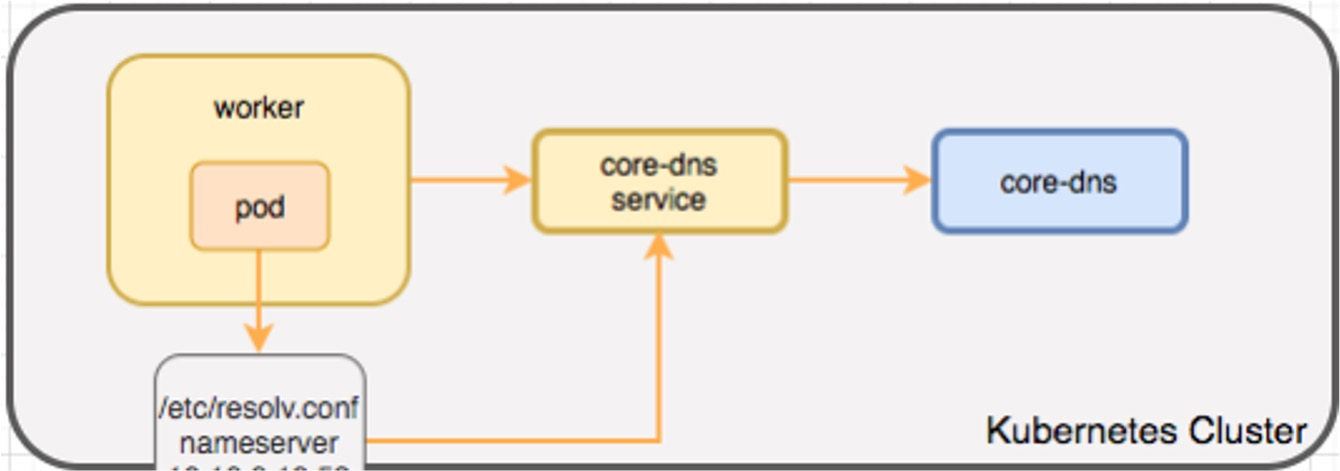

Kubernetes DNS Service

Kubernetes itself provides a service registry in the form of a DNS service. This can be enough for basic usage, but only provides very limited information about the service.

Each service gets the A-Record <service name>.<namespace>.svc.cluster.local. Pods get the A-Record <ip-addr>.<namespace>.pod.cluster.local.

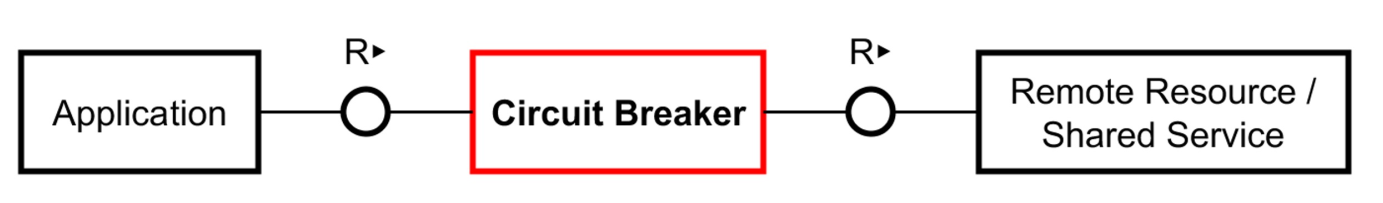

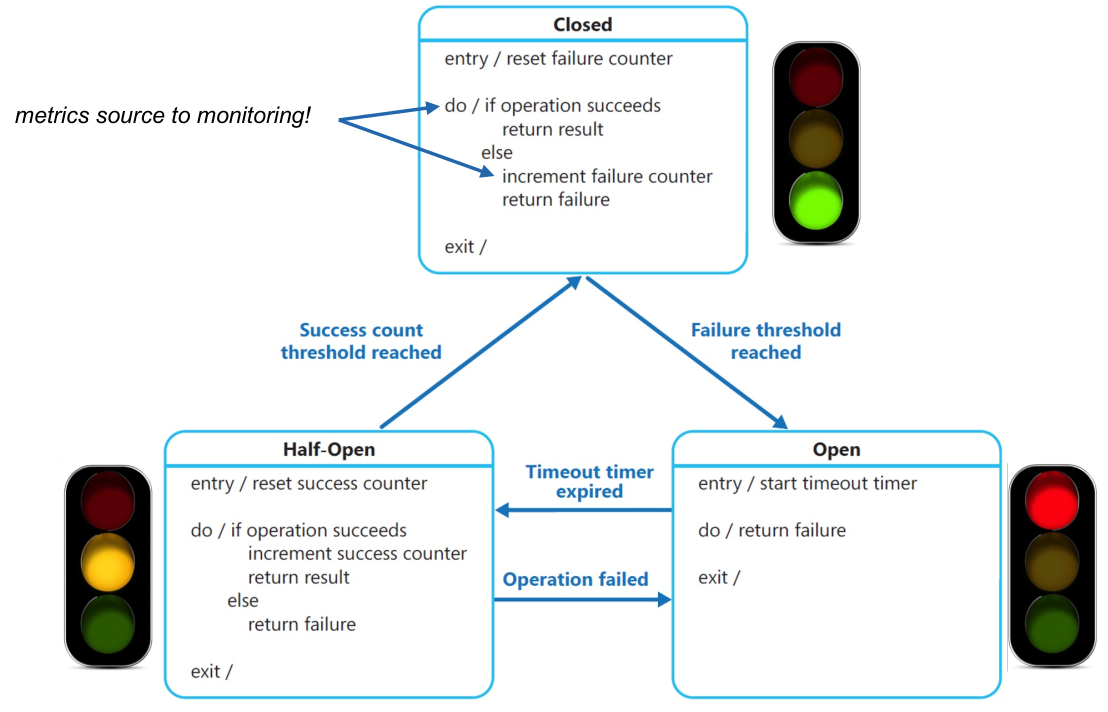

Circuit Breaker

A circuit breaker is an intermediate between consumer and producer which detects if a service is unavailable or unresponsive. This then should lead to stop sending new requests to give the producer time to catch up.

Since the circuit breaker will break the connection and immediately response, this gives the requesting service time to use an alternative (instead of a complicated recommendation algorithm, use a simple average).

If the current state of the circuit breaker is closed, then requests are forwarded to the producer service.

If, when forwarding a request, a failure occurs, an internal counter is incremented. If this counter passes a threshold, the circuit breaker will change into the open state.

In the open state, a timeout timer starts and for this time, the circuit breaker immediately returns an error message. After the timer expired, the circuit breaker changes into half-open.

In the half-open state, only a certain percentage of requests are forwarded. If a certain number of requests succeed, then the state changes back into closed. However, if there are enough failures, the state can change back into open.

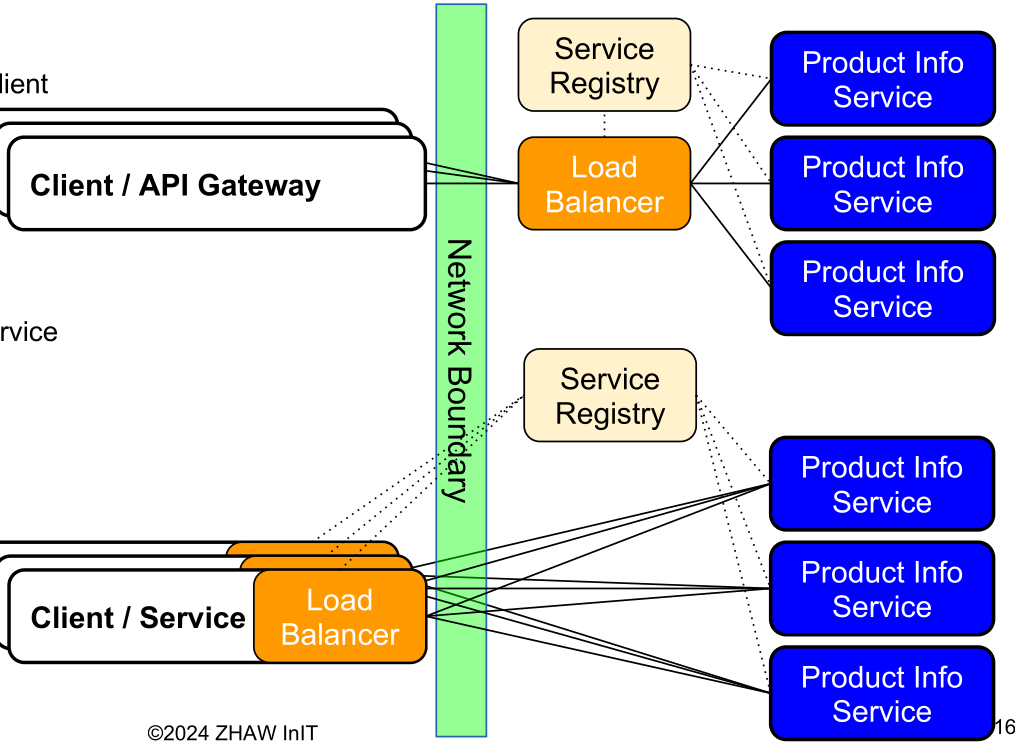

Load Balancer

In a service-oriented architecture scaling is done by starting multiple service instances. However, we still would like to access all of the services with one address and port. As such, a load balancer is a mechanism to distribute the aggregate load to the individual members a pool of Service Instances according to a certain distribution algorithm.

In server-side load balancer, there is one server, which distributes the traffic to the various instances (in Kubernetes, this is done by a distributed load balancer).

Load-balancing can also be implemented on the client-side, giving us client-side load balancing, where each client is accessing the service registry to get a list of all the services and then decide itself which instance to access. This is usually only done for internal services. This eliminates the need of a central load balancer.

There are multiple algorithms with different goals:

- Round-Robin (optimise fairness)

Distributes load equally by assigning requests to instances in turns - Least-Connection (optimises performance)

A request is assigned to the instances with the least on-going request - Source (optimises stickiness)

A request is assigned to the same instance as a former instance

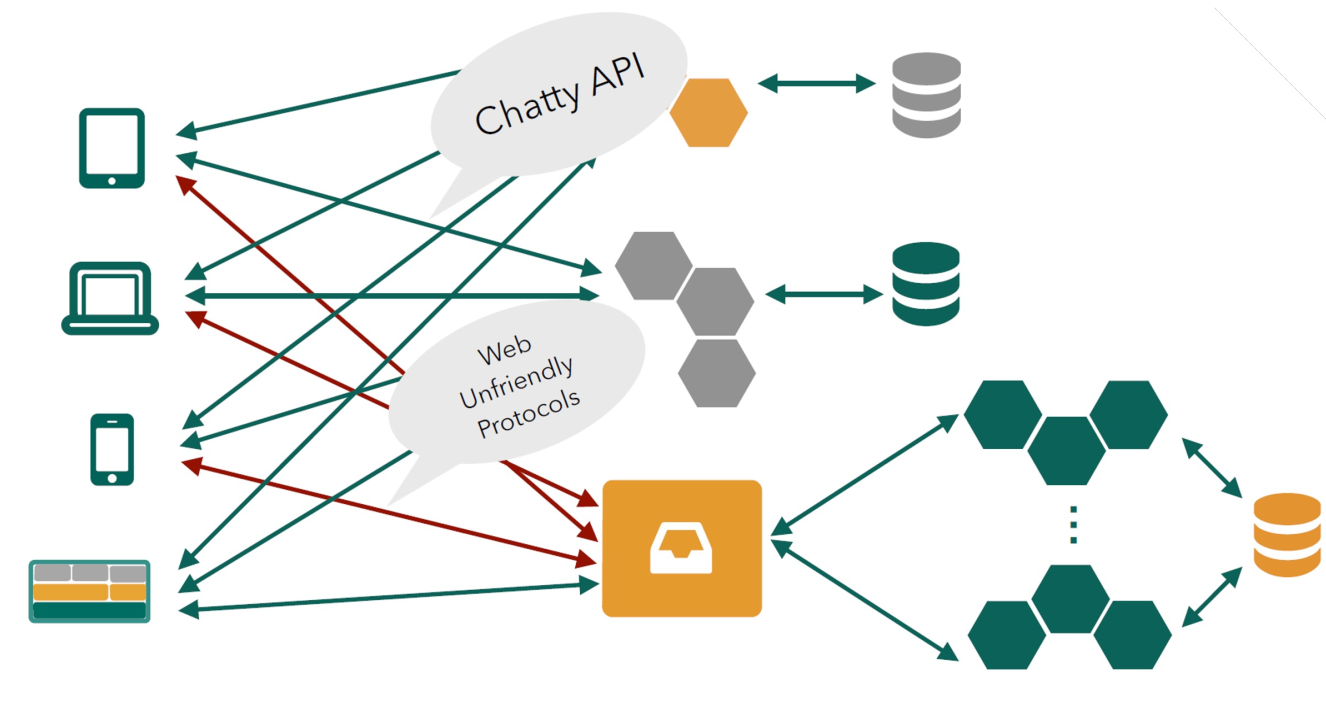

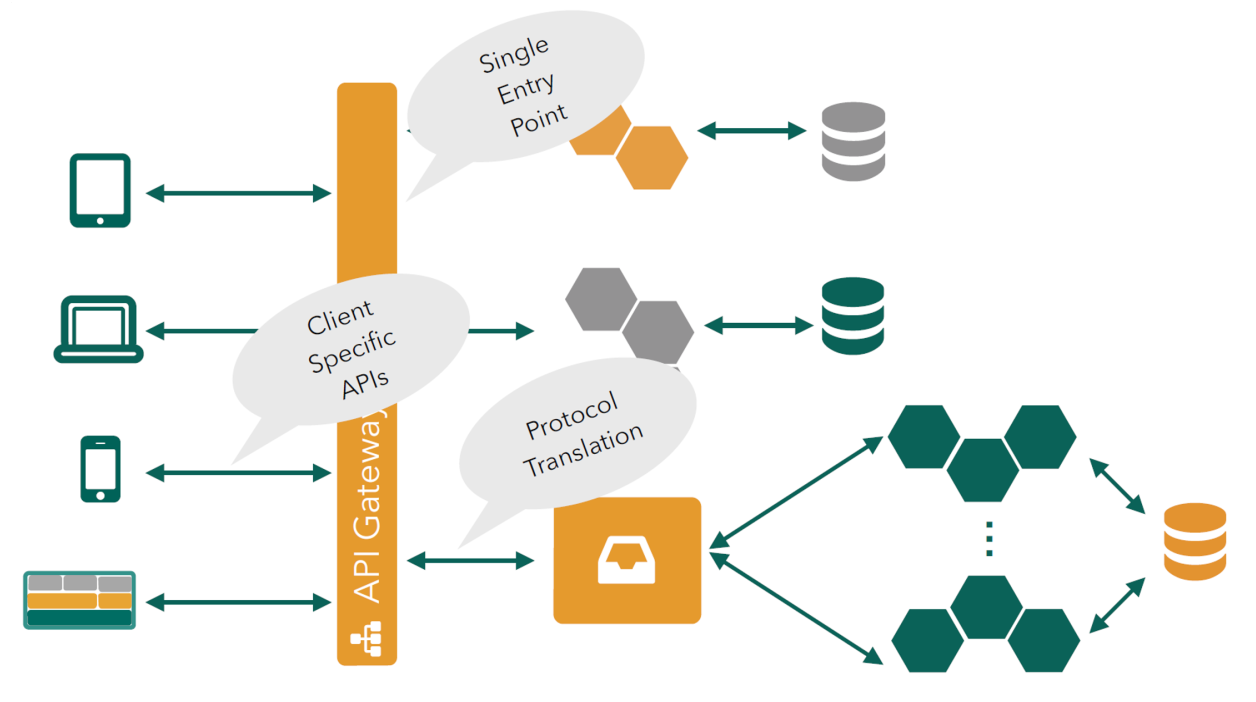

API Gateway

Without an API gateway:

With an API gateway:

A challenge of a service-oriented architecture at scale is to present a consistent API to the consumers. A way to solve this, is to use a API gateway. In away, it is an analogous to the facade pattern.

An advantage of an API gateway, is that the internal architecture is abstracted from the external API and , thus, can be refactored or replaced.

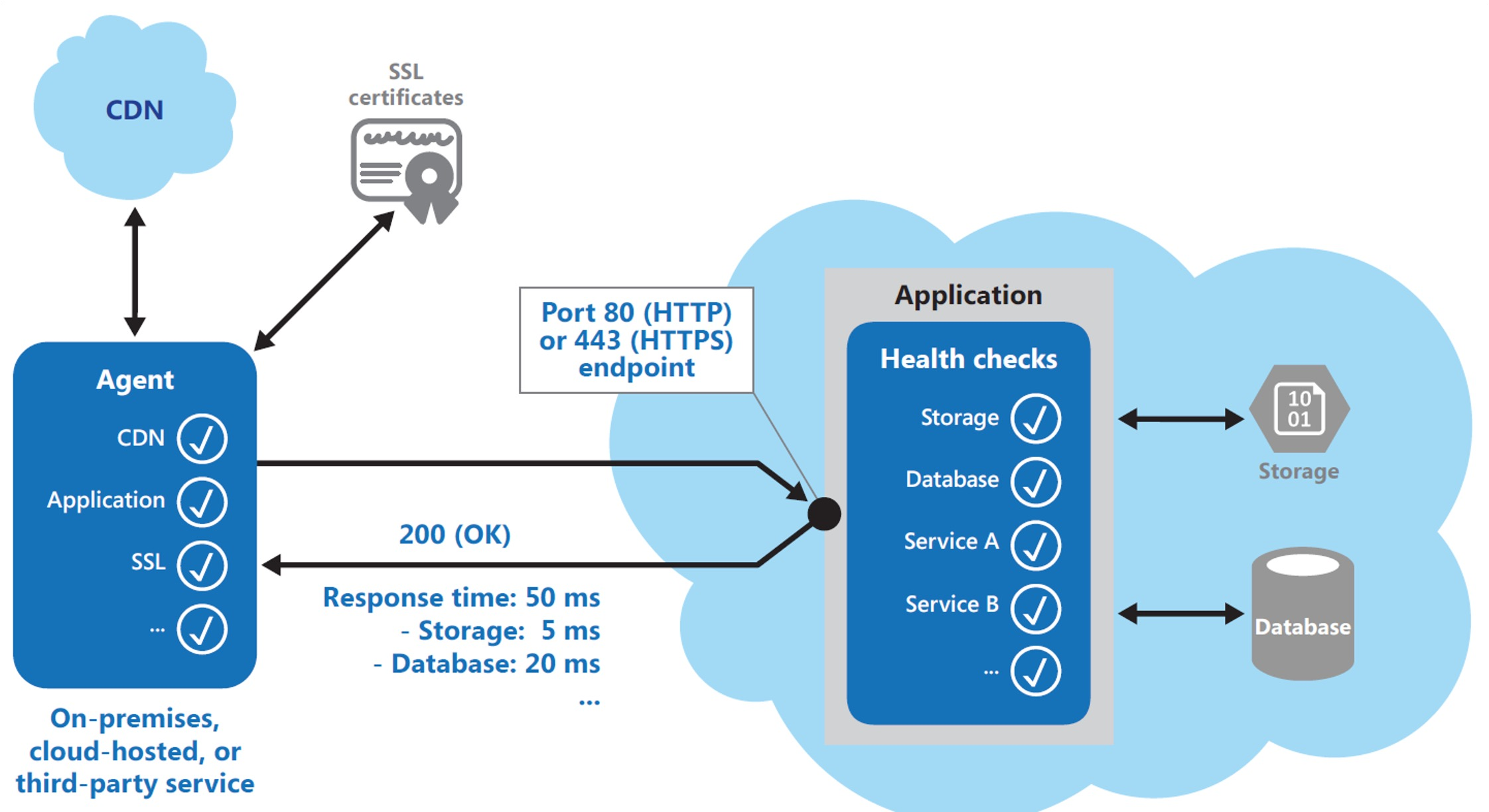

Endpoint Monitoring

Endpoint monitoring checks if endpoints of a service are still up and healthy. This solves the challenge of having a lot of instances and knowing how healthy each service is.

Usually, a service provides a /health endpoint, which reports information about the instance. Typical checks are:

- Verifying internal process status

- Checking the presence of an external backing service (e.g. DB)

- Measuring the response times

- Checking for SSL expiration date

- Validating the HTTP response code

- Checking the content of the response

Health Manager

A health manage ensures that the desired number of instances of each service are operational. For this, it monitors the instance statuses (for example by endpoint monitoring).

A health manager has a desired state and an actual state. The health manager compares the two states and tries to restart, start or stop services to match the two states.

Basically Kubernetes deployments and replica-sets.

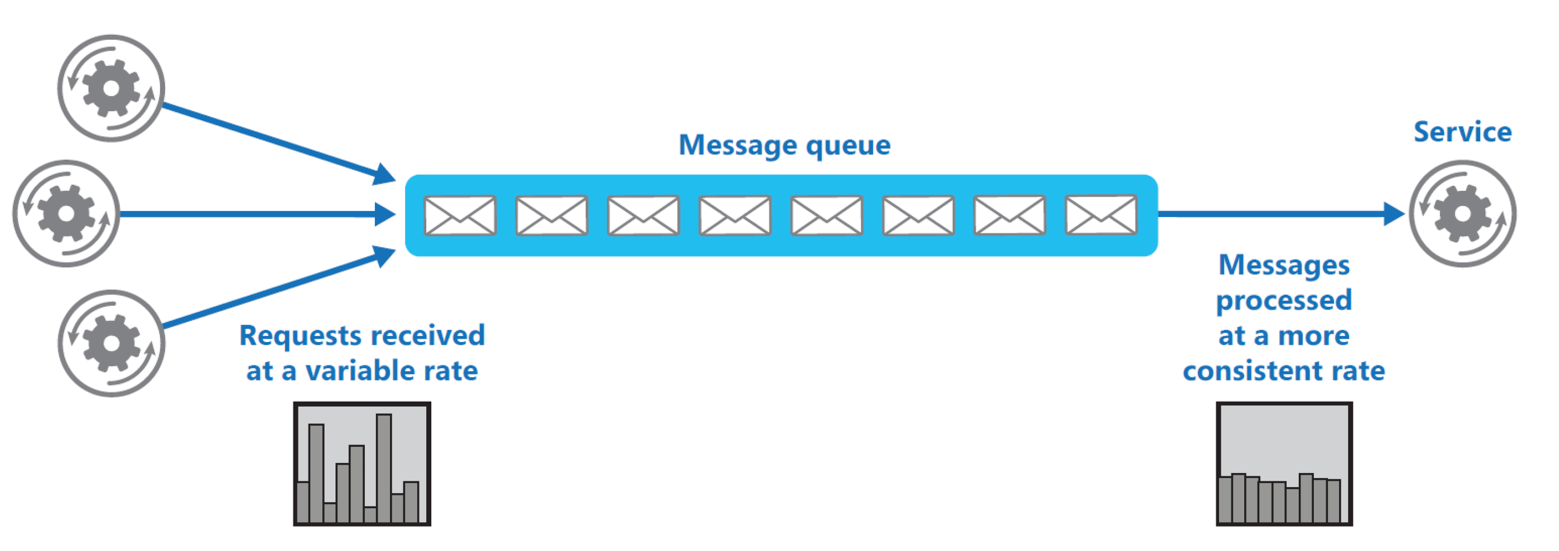

Queue Load-leveling

The number of requests can spike. For non time-sensitive services, requests can be distributed over time. This smooths out the spikes by slowing down some requests. If the peaks are excessive, some requests might be dropped (e.g. returning a 500 status code).

The services can be put behind a load balancer, or alternatively, each service pulls a new request as soon as its done.

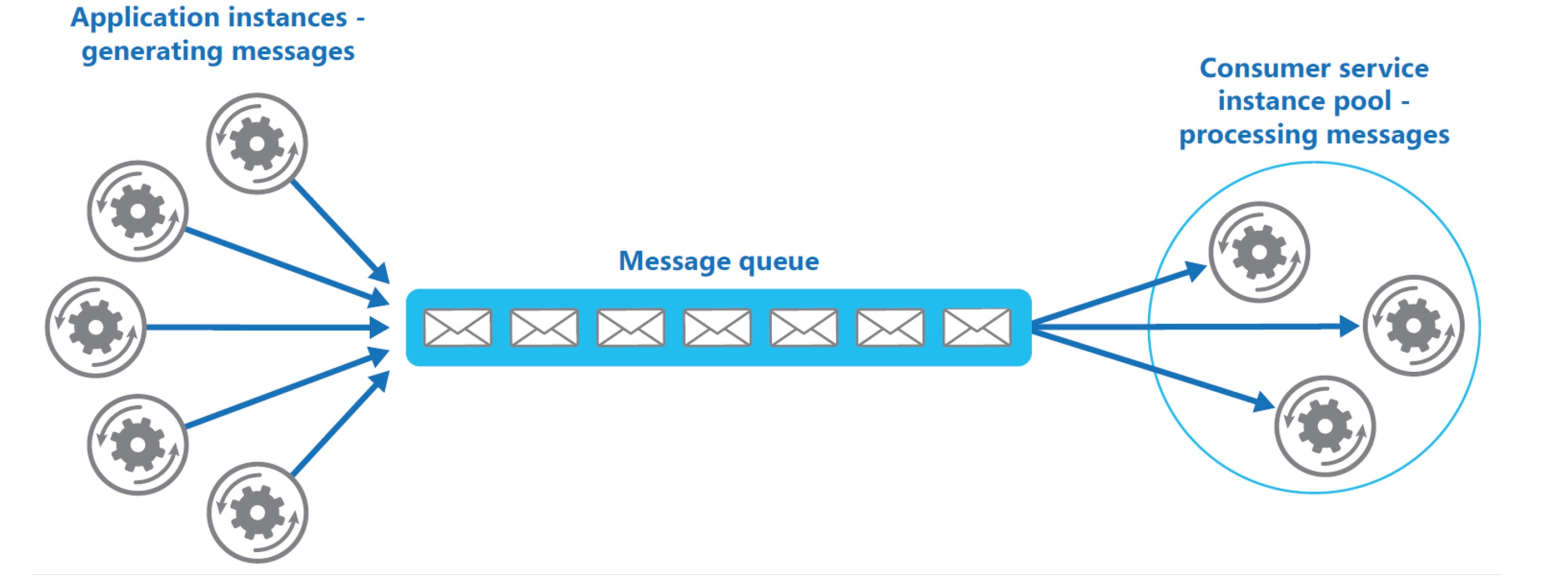

Competing Consumer / Producer

The same mechanism of queue load-leveling can be used to enable elasticity, by scaling up or down the instances based on the amount of messages in the queue, or how quick the queue fills up.

Instead of having a fixed amount of services available, we can also automatically scale the amount of services according to the size of the message queue.

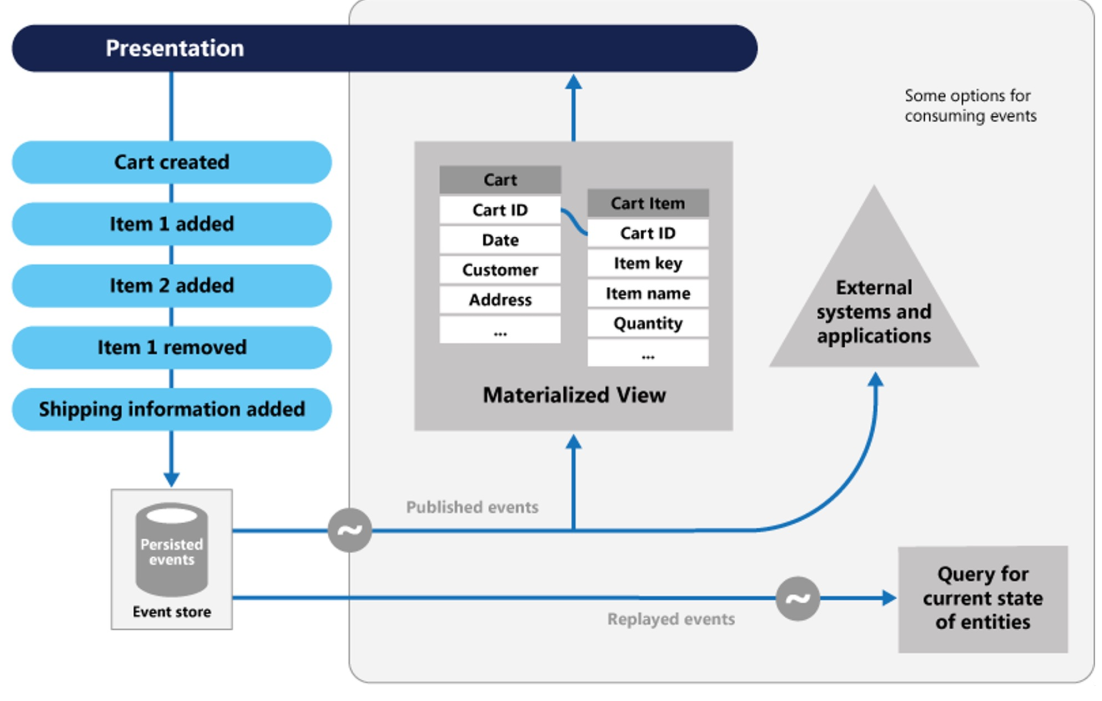

Event Sourcing

Instead of storing the current state, the database stores the individual events leading to changes. This allows one to recreate the state of anytime and gives one an audit trail.

In the materialised view, the current state is stored to allow for quick look-ups for the current state.

This also allows data that is eventually consistent, which can enable heavily distributed systems to track data.

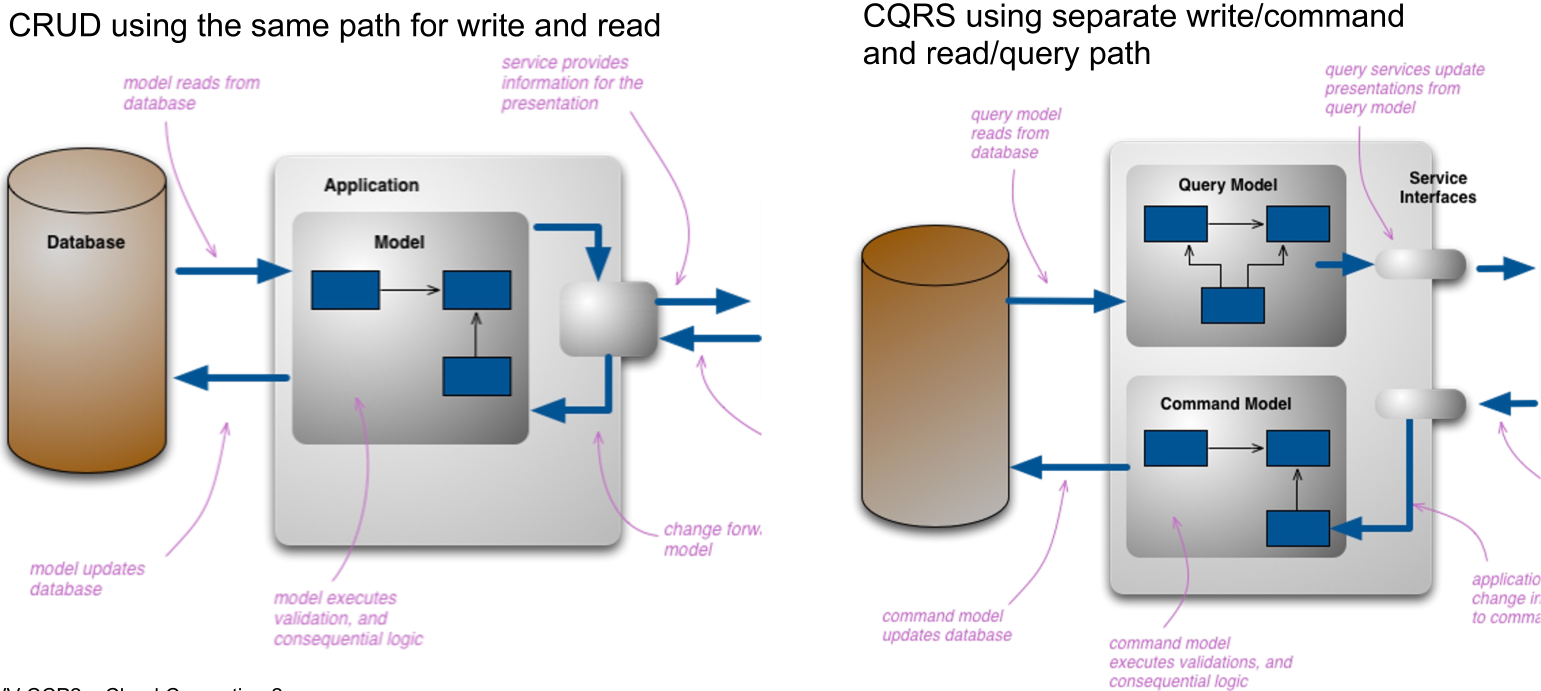

Command Query Response Segregation (CQRS)

One challenge of a service-oriented architecture can be to optimise for read and write operations. The idea behind CQRS is to provide separate paths for write and read operations. This allows to scale the read and write part separately. This is useful for applications which have a disproportionate number of read or write requests.