Basic Game Engine

Engine Management

If there are static classes, these classes have to be created on start up dynamically. However, this means that the startup order is not defined. One solution for this, is a singleton, which creates the instance on demand. This comes with the drawback of performance spikes when a resource heavy system is loaded.

class X {

public:

static X *inst = null;

static X get() {

if (inst == null)

inst = new X();

return inst;

}

public X() {

y_inst = Y.get();

z_inst = Z.get();

//other startup

}

}

A different solution is manualy startup.

void main(int argc, char **argc) {

x_inst = new X(); //order doesn’t matter

y_inst = new Y(); //order doesn’t matter

z_inst = new Z(); //order doesn’t matter

z_inst->initialize(); //this order matters

x_inst->initialize(); //this order matters

y_inst->initialize(); //this order matters

//main loop

//shutdown

}

Game Loop

The game loop has multiple targets.

One interesting note, for targets that do not run on every thread, like AI agents, each entity should have a different offset. This mitigates that issue that there is one frame, where all agents do their path finding and the game stutters because of this.

Callback Driven Framework

The framework calls the frameStart() and frameEnd() method and the programmer hooks into this.

while(true) {

for each(frameListener f){

f.frameStart();

}

// use libraries here

for each(frameListener f){

f.frameEnd();

}

}

Event-based updating

Events are fired when something occurs in the game. One downside is that this makes the game unpredictable, since there could be a sudden spike in events which the game engine needs to handle.

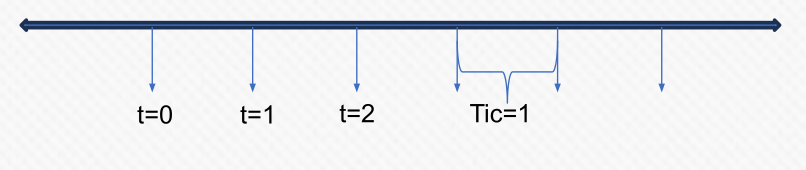

Time

Game engines usually implement a concept of time and measure it in tics. A tic can be set to some arbitrary time span.

The real-time axis is usually tied to the CPU high resolution timer and will be provided by the OS.

The frame-time is defined by the game and can evolve at the same rate as real time. However, the frame time might be paused, stretched, compressed or even reversed.

An other property is if the time line is a global or a local timeline. Global timelines are relative to when the game started, while local timelines are relative to some event in the game (e.g. counting the player being in the air).

This is an example timeline class

class Timeline {

private:

std::Mutex m; //if tics can change size and the game is multithreaded

int64_t start_time; //the time of the *anchor when created

int64_t elapsed_paused_time;

int64_t last_paused_time;

int64_t tic; //units of anchor timeline per step

bool paused;

Timeline *anchor; //for most general game time, system library pointer

public:

Timeline(Timeline *anchor, int64_t tic);

Timeline(); //optional, may not be included

// the method belows will need to lock the mutex

int64_t getTime(); //this can be game or system time implementation

void pause();

void unpause();

void changeTic(int tic); //optional

bool isPaused(); //optional

}

The one interesting method, getTime() should calculate the following (without pausing): \(\frac{currentTime - startTime}{tic}\). If the timeline supports pausing, one has to subtract the amount of time spent paused, both in units of anchor timeline before dividing by tic and in units of this timeline after dividing by tic size

Frame Spikes

One approach to mitigate frame spikes is to use a moving average. The engine keeps track of the last few deltas and computing the average of the those. The moving average is then reported as the current delta. The bigger the delta is, the more robust it will be against spikes. However, it also makes it slower to adapt to actual low changes in the system.

Another approach is to limit the frame rate to a fixed number. Within a small window of that targeted frame rate, the loop is allowed to continue.